ANATOMY OF A “JAG MOVE”:

Carolyn Dwyer on the 2006 Congressional Election

The Back-Story: Of Welch and Waffles

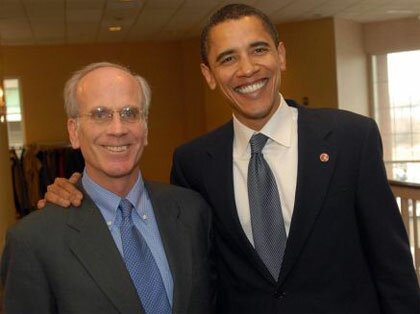

Almost exactly a year ago, I sat down with Congressman-elect Peter Welch for the first in VDB’s series of candidate interviews, that one at Henry’s Diner in Burlington, over eggs and Belgian waffles.

Of course, Welch was merely a candidate then, and not necessarily looking like the odds-on favorite. Burlington Progressive David Zuckerman was threatening a credible third-party challenge, and Adjutant General Martha Rainville was coyly stretching out the “exploratory phase” of her campaign for maximum dramatic effect.

The state’s major media outlets — when they weren’t busy inflating the Zuckerman boomlet — were bobbing their heads in agreement over Rainville: Welch would have a very tough time against the charismatic and telegenic General, they argued, partially because she was extremely charismatic and telegenic, but also because people genuinely liked her and also she looked fantastic on television.

And so we ate waffles, Welch and I.

And I remember being struck with his immediate, yes-or-no answers to what I thought were my four toughest questions: Yes on complete troop withdrawal within a year’s time, yes on firing Rumsfeld immediately; no to both permanent bases and torture, always and forever.

And I remember being struck with his immediate, yes-or-no answers to what I thought were my four toughest questions: Yes on complete troop withdrawal within a year’s time, yes on firing Rumsfeld immediately; no to both permanent bases and torture, always and forever.

That was about all I needed to hear in late 2005.

And I remain convinced that those four positions — stripped to their most binding formulations, and delivered with passion and conviction — eventually won the election for Welch.

Those four positions, and Carolyn Dwyer, of course.

Conventional wisdom holds that even a great campaign manager can’t win an election for you — but a bad one can lose it. And maybe in the other forty-nine states that’s more or less true.

But Carolyn Dwyer has taken the Vermont statewide campaign to an entirely new level of play: nearly flawless execution, marked by unusual discipline and relentless offensive momentum. The mere report that Welch had hired Dwyer buoyed his stock in the media for weeks.

But the true measure of Dwyer’s mojo is this:

During coffee with one of Rainville’s senior staffers, I mentioned that it had been a tough few weeks for their campaign — what with the plagiarism scandal and then the Foley/Hastert scandal — and the staffer just nodded glumly over his coffee.

But when I mentioned the smooth sailing Welch had been enjoying, the Rainville guy suddenly fired up: “Well, yeah, of course — he’s got Carolyn Dwyer running the campaign!”

And he said it like that was cheating, somehow.

So, having begun this past election cycle eating eggs with the Welch campaign, I felt that the only way to achieve real classical narrative closure would be to end it in the same quiet, atherosclerotic way: another sit-down, this time with Carolyn Dwyer, for a post-election post-mortem.

But at the Oasis Diner, rather than Henry’s. Just to keep it even more real.

Vegetarian Burgers, Sharp-eyed Critique, and the Explosive Ethical Question of Cheesecake

Carolyn Dwyer is a unique mixture of introvert and extrovert. A tall, imposing figure, she also has the capacity to fold into herself a bit somehow, to seem suddenly smaller and less intimidating, vulnerable even.

Carolyn Dwyer is a unique mixture of introvert and extrovert. A tall, imposing figure, she also has the capacity to fold into herself a bit somehow, to seem suddenly smaller and less intimidating, vulnerable even.

She can and will track down the managers of opposing campaigns and deliver a stinging rebuke when she feels they’ve gone back on their word, or taken the low road. But she speaks lovingly and at great length about her “magical” staff, and the chemistry they developed over the course of the cycle.

She is “press shy,” she insists, and speaks softly. Until she begins processing strategy, that is.

Then Dwyer’s words begin to stream so fast that even a momentary glitch in attention leaves the listener paragraphs behind her current thought.

Like most longtime campaign types, she can shift gears in the blink of an eye: deliver a long, nuanced critique of her opposition, and then rattle off the script of a sixty-second commercial that might have turned Rainville’s numbers around.

And that is the $64,000 question, for me at least: what went wrong for Rainville, who looked so very good on paper?

And that is the $64,000 question, for me at least: what went wrong for Rainville, who looked so very good on paper?

Dwyer feels that the race was all but won and lost in the six weeks between Rainville’s announcement and the end of the legislative session in Montpelier, when Welch was still serving as Senate President Pro-Tem.

Internal Welch polling showed Rainville up by nearly ten points following her announcement, with “favorables through the roof” — a set of numbers I’d never gotten wind of during the campaign. Rainville had the chance not only to define herself clearly, but to define Welch during that interval.

When she failed to do so, she became the object of ultimately withering scrutiny: with regard to her fund-raising, her use of Guard personnel for campaign work, etc.

But that early paralysis isn’t the only thing Dwyer sees as having doomed the opposition.

Day-to-day execution never came together for them, apparently, even with regard to the simplest details. After calling a press conference to tout their clean campaign challenge, the Rainville camp faxed Dwyer a two-page copy of the pledge — but it arrived only as two blank pages, which Dwyer promptly delivered to reporters as a symbol of Rainville’s sincerity on the issue.

Of the pledge itself, which would have held Welch to the $1 million dollars he had already raised, Dwyer was and is deeply skeptical: “It was an acknowledgment that she couldn’t raise any money.”

Of the pledge itself, which would have held Welch to the $1 million dollars he had already raised, Dwyer was and is deeply skeptical: “It was an acknowledgment that she couldn’t raise any money.”

Of course, more than anything it was Rainville’s tortured positions on the War and Rumsfeld that “put her in a horrible impossible box.”

But Dwyer can’t resist working that Rubik’s Cube herself, even now. “She should have come out in those first six weeks with a strong, clear position on the war. Instead, she stood by the President, stood by Rumsfeld and stood out of step with the majority of vermonters.”

In an anti-war year Rainville continued to salute — and lost by nearly 9%.

That would be the same 9% lead she initially enjoyed over Welch, of course. Talk about classical narrative closure.

Another little known fact: Dwyer points out that in a race where gender was a significant issue, the Welch leadership team was composed of “women and Andrew [Savage, Communications Director]. Manager, field director, finance director, comptroller and scheduler all women. Yet the paid staff was divided equally by gender. Unusual to have a woman campaign manager, much less a staff that is half women.”

Unusual indeed. And undeniably effective.

The Welch campaign’s least likely ethical conundrum?

After weeks of bad press involving checks from PACs associated with Tom Delay and Roy Blunt, Martha Rainville decided to try turning the tables: her campaign launched a critique of Welch, pointing out that he had accepted a small amount from Rahm Emanuel.

It was a weak counter-punch — Delay was under indictment, and Emanuel was the head of the DCCC, and in no legal trouble of any sort — but the Rainville camp just happened to throw it on the same day that Emanuel mailed the Welch camp a cheesecake.

It was a weak counter-punch — Delay was under indictment, and Emanuel was the head of the DCCC, and in no legal trouble of any sort — but the Rainville camp just happened to throw it on the same day that Emanuel mailed the Welch camp a cheesecake.

The excellent expensive very creamy sort of cheesecake — as a way of saying keep up the good work.

According to Dwyer, there was a hurried brainstorming session in her office about the possible ramifications of eating the cheesecake. Heated arguments pro and con. Could this be the micro-issue that crippled a campaign loping to victory?

Finally, the decision was made to snarf the cheesecake.

Dwyer tells these sorts of stories fondly, with the relaxed style of a winning campaign. But not every topic goes down easily, even now, weeks out from the race.

Mid-way through her vegetarian burger, and fully worked up, for instance, Dwyer can’t resist listing and popping a series of persistent myths about the election: that the race was very close (“When is 9 points anything other than a comfortable win?”), that Rainville lost because it was a bad year for Republicans (“This was a year when Douglas and Dubie took over 50% of the vote”), and that Rainville ran a “good” campaign (“Just because you don’t go negative doesn’t mean you ran anything like an effective campaign”).

The final myth? That Rainville is nice-nice.

“She never conceded,” Dwyer says, raising her eyebrows significantly. Even hours after all the major networks had called the race overwhelmingly for Welch, no phone call came in from Rainville.

Well after 10 pm, with the window for local television coverage pressing, Dwyer eventually put in a call herself to a Rainville staffer. More time passed.

Finally, at the last moment, Rainville did call back for Welch, but managed to leave Welch wondering when he hung up the phone whether the race was actually over or not.

“It was a jag move,” Dwyer says, shaking her head.

A jag move? Like a tweak, a poke in the eye with a sharp stick?

“Yeah,” Dwyer explains, “a jag move. A low-rent move. Like if you’re drinking water, and your friend’s drinking vodka, and you switch glasses when they’re not looking and then you drink their vodka. And they’re stuck with the water. That’s a jag move.”

Even the memory of it seems to tick Dwyer off a bit, so much so that her eyes take on a sudden, faintly predatory light.

And I realize that this may in fact be the single-most enduring lesson of the 2006 Vermont election cycle: win or lose, you jag-move Carolyn Dwyer at your peril.

[This piece appeared first in The Vermont Guardian.]

But without missing a beat she began to evangelize for Obama, whenever she picked up the phone, or sold someone a block of feta. “Oh yes, and we have the Obama-rama going on in the back,” she’d offer, along with the newly-installed wi-fi system, and the belly dancing on the 13th of January.

But without missing a beat she began to evangelize for Obama, whenever she picked up the phone, or sold someone a block of feta. “Oh yes, and we have the Obama-rama going on in the back,” she’d offer, along with the newly-installed wi-fi system, and the belly dancing on the 13th of January. Now, VDB broke from the Lutheran Church in a schism of one back in 1974. At issue was one of the Miracles of Elijah, in which the Lord sends bears to maul a group of children who have mocked Elijah for being bald.

Now, VDB broke from the Lutheran Church in a schism of one back in 1974. At issue was one of the Miracles of Elijah, in which the Lord sends bears to maul a group of children who have mocked Elijah for being bald. But VDB has always aimed to go a step beyond: we continue our coverage, long after the GOP have taken their thumping, and the klieg lights have gone dark.

But VDB has always aimed to go a step beyond: we continue our coverage, long after the GOP have taken their thumping, and the klieg lights have gone dark.

But Stewart, as with all the Rainvillians, had a touching faith in Martha’s personal charisma.

But Stewart, as with all the Rainvillians, had a touching faith in Martha’s personal charisma. “WASHINGTON, Dec. 12 — Saudi Arabia has told the Bush administration that it might provide financial backing to Iraqi Sunnis in any war against Iraq’s Shiites if the United States pulls its troops out of Iraq, according to American and Arab diplomats.”

“WASHINGTON, Dec. 12 — Saudi Arabia has told the Bush administration that it might provide financial backing to Iraqi Sunnis in any war against Iraq’s Shiites if the United States pulls its troops out of Iraq, according to American and Arab diplomats.” If you’ve missed the back-story here, it’s short but sweet: Obama’s middle name is “Hussein,” and he is a registered Democrat. And it doesn’t take a towering intellect like Brit Hume to figure out what that means — clearly Obama is a stalking horse for terrorist interests world-wide.

If you’ve missed the back-story here, it’s short but sweet: Obama’s middle name is “Hussein,” and he is a registered Democrat. And it doesn’t take a towering intellect like Brit Hume to figure out what that means — clearly Obama is a stalking horse for terrorist interests world-wide.

And I remember being struck with his immediate, yes-or-no answers to what I thought were my four toughest questions: Yes on complete troop withdrawal within a year’s time, yes on firing Rumsfeld immediately; no to both permanent bases and torture, always and forever.

And I remember being struck with his immediate, yes-or-no answers to what I thought were my four toughest questions: Yes on complete troop withdrawal within a year’s time, yes on firing Rumsfeld immediately; no to both permanent bases and torture, always and forever. Carolyn Dwyer is a unique mixture of introvert and extrovert. A tall, imposing figure, she also has the capacity to fold into herself a bit somehow, to seem suddenly smaller and less intimidating, vulnerable even.

Carolyn Dwyer is a unique mixture of introvert and extrovert. A tall, imposing figure, she also has the capacity to fold into herself a bit somehow, to seem suddenly smaller and less intimidating, vulnerable even. Of the pledge itself, which would have held Welch to the $1 million dollars he had already raised, Dwyer was and is deeply skeptical: “It was an acknowledgment that she couldn’t raise any money.”

Of the pledge itself, which would have held Welch to the $1 million dollars he had already raised, Dwyer was and is deeply skeptical: “It was an acknowledgment that she couldn’t raise any money.” It was a weak counter-punch — Delay was under indictment, and Emanuel was the head of the DCCC, and in no legal trouble of any sort — but the Rainville camp just happened to throw it on the same day that Emanuel mailed the Welch camp a cheesecake.

It was a weak counter-punch — Delay was under indictment, and Emanuel was the head of the DCCC, and in no legal trouble of any sort — but the Rainville camp just happened to throw it on the same day that Emanuel mailed the Welch camp a cheesecake. And Dwyer’s effectiveness is only enhanced by her knack for avoiding the spotlight herself. There is no photo accompanying this post for good reason.

And Dwyer’s effectiveness is only enhanced by her knack for avoiding the spotlight herself. There is no photo accompanying this post for good reason.

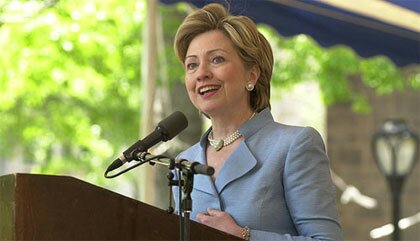

By really closely, I mean I’ve read well over forty books about them, as well as every press account and journalistic chin-puller I could get my hands on. Written a novel about Bill Clinton, and reviews of each of their very bad autobiographies.

By really closely, I mean I’ve read well over forty books about them, as well as every press account and journalistic chin-puller I could get my hands on. Written a novel about Bill Clinton, and reviews of each of their very bad autobiographies.

The Humiliation (let’s go ahead and capitalize) will be of an order exceeding Dean’s death-by-a-thousand-screams. And the events themselves will be shaped by the logic of the public’s need for that humiliation.

The Humiliation (let’s go ahead and capitalize) will be of an order exceeding Dean’s death-by-a-thousand-screams. And the events themselves will be shaped by the logic of the public’s need for that humiliation.