The Brigadoon Fundraiser of 2007: Trailing Barack Obama Through an Event That Never Happened, In the Middle of a Presidential Campaign That Was Meant to Be

To Begin With: Revisiting the Obama Effect

When Barack Obama came to the University of Vermont a year and a half ago, to campaign for Bernie Sanders and Peter Welch, he drew a crowd so large that campaign workers eventually had to seal the doors of Ira Allen Chapel.

Those who didn’t make it inside then swarmed the overflow venue to the point where it too had to be sealed, for safety reasons.

Thousands, of course, didn’t make it into either location. But they didn’t just grumble and melt away.

Instead, they clustered around the entire Chapel, two or three deep. And even after Obama and Sanders and Welch came out to address them through a bullhorn, many refused to leave when the event inside actually got underway.

Instead, those remaining congregated around the Chapel windows, drumming on the glass with their fists by way of applause.

It was my first introduction to the Obama Effect, and it was a learning experience.

Among other things, I learned that even when rigidly managed, attendance at any Obama event will rapidly spiral out of control.

I learned that the tall Chapel windows can apparently bear the weight of a full-grown Vermont man, drunk on hope, without shattering.

And I learned that I am personally willing to lie or feign injury in order to get into any venue where Obama will be speaking. The Chapel event was a comparatively easy nut to crack: I happened to know a back entrance, with an unused freight elevator.

My one regret about that Ira Allen event is that although I heard Obama speak, and it was a speech very much worth hearing, I never got to say hello, never got the chance to look him in the eye and shake his hand.

But that was eighteen long months ago, and times have changed.

Obama is now not simply a candidate for President, but an incredibly successful candidate: national polls show him running a solid second to Hillary, while his fundraising has outpaced the efforts of Hillary and Bill Clinton and Terry McAuliffe combined.

In June, Obama agreed to accept a twenty-four-hour Secret Service detail — a precaution never before taken in advance of the first primary.

In short, trying to stage a meet-and-greet with Obama in August of 2007 was no longer child’s play. It was now, for all practical purposes, impossible.

Which left only impractical purposes — better than nothing, as purposes go.

The Brigadoon Fundraiser:

You Could Attend, But Then We’d Have to Kill You

About a month and a half ago, I got word that the Obama campaign would be holding a fundraiser on the 12th of August, in Southern Vermont. Better yet, Obama would be attending, as would the state’s entire Congressional delegation.

But it was a tricky word that I got. The person who told me about it instantly made it clear that I now needed to forget I’d ever been told. “You can’t tell anyone about the event,” the person said, sotto voce. “Not a word. Nothing. To no one.”

“But I thought the point of a fundraiser was to, you know, spread the word,” I said, lowering my own voice.

“Don’t worry about the word,” the person whispered, reaching across the table for the parmesan cheese. “Believe me, the word isn’t the problem.”

And so it went. For the next month and a half, no one mentioned this fundraiser to me, and I mentioned it to no one. Even when I met other Obama supporters, hard-core types I knew would have to know if anyone knew, the subject never once came up. In fact, it almost ceased to exist as a possibility, to the point where I began to question my own memory. Even the person who had told me about it originally told me nothing more about it.

It was like Brigadoon, this event, looming up out of the mists, shimmering faintly, and then vanishing without a trace. Until days before the event, when I got an email specifying the time, the date, and the place.

And nothing else.

In the Heart of Norwich: Storming the White Tent

Turned out that Neil Jensen, the driving force behind Vermonters for Obama, had also secretly signed up for this event, and secretly signed his wife Gabrielle up as well. So the three of us carpooled together down to Norwich, which was a great deal of fun but it did mean that my mild paranoia about the event itself was gradually amplified by theirs over the hour and a half in the mini-van.

And what sane person wouldn’t be paranoid?

We didn’t know even the most basic things about the event, after all — like whether we would be allowed inside. Or whether it would, in fact, take place. Those sorts of things.

So when we drove slowly up the leafy road toward the site, and we spotted a bunch of people grouped around a thicket of Obama signs and a short yellow school bus in an empty parking lot, Neil began to turn in.

“They’re probably shuttling people in from down here,” Neil said.

Immediately Gabrielle reached over and cranked the wheel back the other way. “Keep driving,” she hissed. “Who knows what happens when they get you on that bus.”

I had to agree: we were so close now, and there was no reason to risk getting on a bus and being driven over the line into New Hampshire and dumped there on the streets of Hanover after dark.

So we drove up to the house, and parked beside the short line of cars that had also evaded the short bus/venus flytrap stop down the road. Beside the Stetsons’ brick house a massive white tent had been erected, with two spires rising some thirty feet in the air. Under the tent, it was cooler and a little dark, with large white Chinese lanterns glowing up in the rigging.

A jazz band was working on the stage, a nice laid-back outfit filling in the background. But like everything else about the evening, even the band had odd hidden power — at one point I noticed that the saxaphone player had been playing the same note for a good three minutes running.

“Circular breathing,” Neil explained over the music. “Sonny Rollins can go half an hour on a note like that.”

But even though the musicians had apparently dispensed with standard breathing, we acted like nothing was out of the ordinary: cadged some drinks, sampled the smoked cheddar cubes, and swapped odds on whether Obama would actually appear.

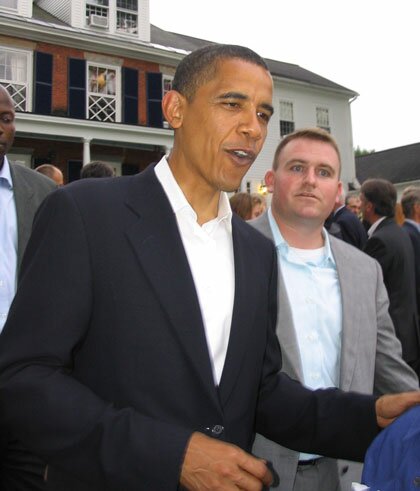

And right at that moment he did, up on the steps of the Stetsons’ house.

Now, trying to meet a famous actor or politician in the middle of a crowd gathered in their name is an arcane art, not susceptible to logic. Why? Because it’s like watching a drop of water streak down your windshield: you may think you know where it will finish, but you don’t, because along the way a hundred small impurities on the glass will nudge it to the right, and then the left.

So plotting a straight line through the crowd, and standing somewhere along that line, doesn’t work, nine times out of ten. Capillary action will carry the headliner somewhere twenty feet off to your right, and by that time there’s not a damn thing you can do about it.

Which is to say that the spot I picked was dead wrong, by a good ten feet — there were twenty people between us. And I was just coming to terms with that fact when Obama spotted something off to his left, and said loudly, “Uh oh, look out for this guy.” And then he turned to hug Bernie Sanders, who had loomed up quietly beside him.

But the thing is that when he and Bernie broke their clinch, and Obama turned back to the crowd, somehow he was suddenly pointed right at me.

Now, I prepared two questions days before, one fast-pitch and one change-up, on the assumption that I would only get three minutes maximum with the guy. The change-up was a literary question, and in addition to giving him a chance to relax and talk about something other than political strategy, it was a question to which I could really use an answer.

“I’m teaching Dreams From My Father [Obama’s autobiography] in a postmodern American literature class in the spring,” I told him, “and I think I know what I want to say about it. But if you were teaching it, what would you want to dwell on that people tend to miss? How would you want it taught?”

It had almost exactly the effect I was after: Obama widened his eyes, and stopped completely and thought for a minute, a little smile playing at the corners of his lips. And then he gave me a beautiful, carefully formatted answer, just like that.

“I think what I’d want stressed is that the patchwork formation of identity, that I talk about in the book, is a quintessentially American phenomenon, as well as modern, or postmodern. That questioning about who you are is another way of talking about the limitless possibilities of who you can be in America, how many elements and strands can make up your identity. So when the book turns to Africa at the end, there’s the sense that in addition to Africa having something to say to me about who I am, my roots, America has something to say to the world about how we can conceive of ourselves as individuals.”

More or less the same response George W. Bush might have given, in the same circumstances. Although Bush might have sounded a touch more erudite.

And then Obama’s gone, because the show is about to start.

Under the Big-Top:

Obama and “The Consciences of Vermont”

This was no cut-rate Brigadoon. As promised, the entire Congressional delegation took the stage with Obama: Peter Welch, Bernie Sanders, and Pat Leahy, along with Jane and Bill Stetson, the hosts.

Again I was struck, as I often am, by the absolute solidity of our Washington line-up. Peter Welch has found a way to infuse his speeches, even the short hits like this one, with a buoyant energy that drives his critique of the Bush Administration along at a tremendous clip — the effect is optimistic and up-beat, although most of the applause lines are unabashedly critical, real red meat.

Bernie, like Leahy, has worked with Obama in the Senate, and his praise of his colleague was tinged with an authentic affection. And when Leahy took the stage, there was a bantering and an ease that told you there was more at work there than just getting elected.

There was actual friendship, all the way around. You could tell by the jokes.

Leahy, for instance, responding to several compliments directed toward his wife Marcelle, went for the self-deprecating remark (“Actually the thing that I’m always flabbergasted by is that Marcelle would have me”) only to have Obama deprecate just a wee bit more (“You know, we’re all flabbergasted by that too, Pat”) — which left Leahy with the straight man’s finish (“I guess it’s all downhill from here, folks”).

But things got serious again by the time Obama himself began to speak. He thanked the organizers of the event, the Stetsons, Charlie Kireker, and Carolyn Dwyer. “No one out-organizes Carolyn Dwyer,” Obama said emphatically, pointing out into the crowd, “and we love Carolyn.”

And then he summed up the three men that had come before him in a perfect phrase — “these men are the consciences of Vermont, in the House and the Senate.”

Any Obama speech is notable for the low, easy-going, rolling quality that marks its first ten minutes. For all of his reputation as a barn-burner, Obama always starts slow and steady, voice low. Even when talking about the controversy with the Clinton camp over foreign policy, Obama stayed in second-gear: “Now, they’ve been making a big fuss over the fact that I said I would meet not just with our friends, but with our enemies. And I would do so without preconditions.

“But you know, they’re confusing preparation with preconditions. Of course, I will prepare for these meetings, and I won’t pull any punches in the meetings. But that’s different from setting preconditions. It doesn’t do any good to say, we’ll talk to you, but only after you accede to all of our demands. We can’t demand that our enemies come to us first as vassal-states. Now, I’ll tell you — I’m not worried about losing a PR battle with Kim Jong-il. Because for one thing, I’ve got a better haircut [laughter]. And for another, I’m not starving my own people. So I think we can handle that PR initiative.”

And then he launched into an idea that I know he’s spoken about before, but this was the first time I’d heard it played out: an Islamic summit, called by an American President, and held in a Muslim country.

“It will be held in a Muslim country, and I will show up,” Obama said pointedly, and I wondered suddenly why that seemed like such a radical promise to make.

The Final Question:

In Which Pat Leahy Takes Pity on the Socially Challenged

Near the end of Obama’s speech, I drifted out of the big-top and began a long, looping walk back to the rear of the tent. The thing was that I still had one question I felt I should ask, the fastball, and I figured I’d try one last time to act like a real high-buck journalist: I’d stake out the rear exit, and be standing on Obama’s exit path when he finished the speech.

But as noted above, I suck badly at this sort of computation.

And so, as Obama exited, he shook hands and chatted with three or four people standing just outside the tent flap, and then he executed a little sidestep that allowed him to take another, less crowded route back toward the Stetsons’ kitchen. So that’s that, I figured, and I watched the man make his slow, skillful getaway.

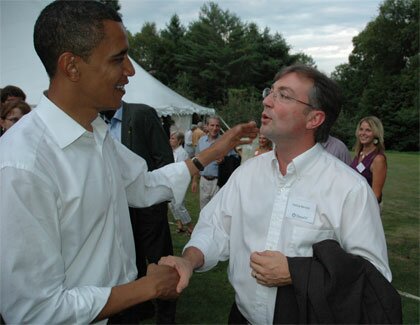

And that’s when there was a tap on my shoulder. I turned, and it was Pat Leahy.

“Are you trying to say hello to Barack?” he asked, and before I could stumble out an answer Leahy reached over and snagged an expensive looking camera out of the hands of an aide. He quickly ran his fingers over the controls, and then called the signals: “Okay, I’ll introduce you to Barack, and then you step in and shake his hand, and I’ll snap the photo. How’s that sound?”

It sounded fairly good.

And that’s precisely what he did: as Obama was breaking off with another guest, Leahy put a hand on his shoulder, swung him around, introduced us, stepped back like a photojournalist for the Washington Post and snapped what is now my favorite photograph of all time, for lots of reasons, but the photo credit itself being one.

There was nothing left to do but ask Obama the last of my questions, the one I knew he didn’t want to answer, but the one that arguably shadowed everything.

“There’s been a fairly consistent dynamic in the polls nationally,” I started out, “with you and John Edwards seeming to split what might be called the change vote. Together your totals outweigh Clinton’s lead in most every state, and in a normal primary season, one scenario would have Edwards eventually dropping out, and you consolidating that change vote. But with the calendar so viciously frontloaded, it’s hard to imagine anyone dropping out before the bulk of states go to the polls. Is there time enough to make that move past the Clinton campaign? And how is your campaign looking at that persistent three-way dynamic, and do you have a strategy to bust it open?”

I was right; it was one of the questions he didn’t want. Where my earlier question about Dreams From My Father had brought him to a complete stop, and made his face open up, now he began turning and moving on almost before I’d finished, eyes a little hooded.

“We’re confident that the results out of Iowa will be definitive enough so that the dynamic you’re talking about won’t be any issue,” he told me. “We feel really good about the organization, and the progress we’re making there. And I think that’ll take care of it.”

He smiled then, and nodded, and he was gone for good.

And by the time I’d wandered back to the bar for a last beer, so was Brigadoon: the vast tent was now nearly empty, night and the pine forest closing in, just Neil and Gabrielle and I trying surreptitiously to squirrel away enough smoked cheddar cubes between us to last the long ride home to Burlington. Off in the distance, we could see Bill and Jane Stetson saying a few last gracious goodbyes beneath the light at their front step.

Nothing left anywhere in Norwich but hope. Just raw hope in Iowa, hope that the people there say it loud at the polls.

But it didn’t feel like a small thing with which to be left, really.

In fact, with a growing national army of supporters like these — able, good-hearted people who can produce a major event like this out of thin air, people who don’t necessarily need to breathe when they play the saxaphone — hope didn’t seem audacious at all.

It seemed inevitable, like the way things must come to be.

[Many thanks to the quick-draw photographers who contributed so much to this post: Dottie Deans, Sue Kavanagh, Senator Patrick Leahy, Mary Sullivan, and Will Wiquist.]