The Cheetah (Briefly) At Rest: The 2006 VDB Interview With Matt Dunne

Campaign 2006: The Cheetah (Briefly) At Rest

Matt Dunne Slows Down Long Enough to Discuss Bill Clinton, Brian Dubie, and the Suddenly Smoking Contest for Lieutenant Governor

Earlier this year, I spent some time following Matt Dunne as he went door to door, in Burlington’s Ward 4, a neighborhood not too far from my own. Most of the houses are small, neat affairs, with meticulous lawns, often tended by retired men and women on fixed incomes, whose cars sport yellow ribbons and faded “Bush/Cheney 2004” stickers.

It is not ordinarily considered a bonanza of Democratic votes, this end of Ward 4. Yet there was Dunne, ignoring the voter-ranking sheets his intern was carrying, simply knocking on every door although he had to know that many of those peeking through the curtains had been voting Republican long before George W. Bush was littered.

It is not ordinarily considered a bonanza of Democratic votes, this end of Ward 4. Yet there was Dunne, ignoring the voter-ranking sheets his intern was carrying, simply knocking on every door although he had to know that many of those peeking through the curtains had been voting Republican long before George W. Bush was littered.

Finally, Dunne spotted four older men and women sitting in lawn chairs, tending a forlorn little tag sale just inside a dimly lit garage. The intern saw immediately what was about to happen, and she whispered fiercely, “Don’t do it, Matt,” but Dunne was already powering up the spiffy new asphalt driveway.

To the intern’s obvious horror, the garage sale stop lasted nearly thirty minutes — an insane amount of time to spend on four potentially hostile voters — but when the dust had settled two things of moment had transpired.

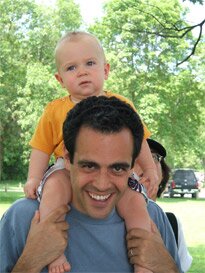

First, Matt Dunne had purchased a stuffed llama for his infant son, Judson, for the asking price — $1, no haggling. And second, one woman of the four had let it slip that she “couldn’t see how Dubie had done all that much, really,” and would give what Dunne said about a full-time Lieutenant Governor “some thought.”

And that was enough for Dunne to go away an almost completely happy man. The man VDB long ago dubbed “The Cheetah” — in a nod to his restless and hungry campaign style — clearly won’t stop until he somehow manages to bring his political vision to every voter in the state, regardless of party, regardless of the odds or the conventional wisdom.

And that vision — a full-time Lieutenant Governor occupying an “office of action” — has begun to resonate, and powerfully so. Jim and Liz Jeffords gave Dunne their endorsement just yesterday. And both the Burlington Free Press and the Vermont Troopers Federation recently flipped their endorsements from Dubie to Dunne, twin seismic events on the Vermont political landscape.

Dubie, according to the Free Press, has been “disengaged” this campaign season, cancelling debates, ignoring the traditions of Vermont politics in favor of a modified Rose Garden strategy.

(And speaking of “disengaged,” Dunne has posted a devastating voice mail — Dubie’s secretary explaining that the Lieutenant Governor won’t be coming into the office between August and January. As smoking guns go, it’s fairly smoky.)

But with polls showing Dunne closing very quickly, you can bet Dubie’s engaged now. Oh, yes. Any more engaged, in fact, and the guy will have cheetah prints running up the seat of his otherwise spotless khakis.

A possibility captured brilliantly in

* * *

VDB: So I want to begin with something that’s been a real, long-time point of fascination for me, and that’s Bill Clinton.

Dunne: Sure.

VDB: I wrote a book about him — as you know because I forced a copy on you a few years back — and the book centers on this photograph, which you know fairly well, I’m sure. It’s Clinton shaking hands with John F. Kennedy in July, 1963, and I always think of it as the “Sword in the Stone” photograph. Because when Clinton released it in 1991, or 1992, it made this compelling visual case to people, because here was Clinton as a boy shaking the hand of JFK, the martyred icon of the Democratic Party.

It was as though the sword had been passed in that moment.

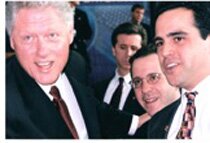

And it really made an emotional case for the unknown Clinton. Now, in your first TV ad, you used a picture of yourself with Bill Clinton. So — and I’m hoping you can lend me the photo so I can throw it up on the website — I was wondering if you could talk for just a minute about that photo of yours.

Who’s in it, what’s going on, where was it, the look on your face, the look on his, what’s happening?

Dunne: Sure. It was an interesting moment. I had been on the job at AmeriCorps/VISTA for, I think, five days. And I got a call at about seven o’clock at night, as I was still figuring out my new responsibilities, from the domestic policy office. And the call was informing me that we were doing a “Bridging the Digital Divide” event the next morning with Steve Case, head of AOL —

VDB: Oh, that Steve Case.

Dunne: — and Bill Clinton, and [Face screwed up in disbelief] me, you know, at Blue High School in Southeast Washington [Laughing now]. And they were going to call me back in a few minutes to get more details on VISTA and the Bridging the Digital Divide Initiative, which we had been undertaking for a little while, and I was actually brought in to the Clinton administration because of my technology background, as well as my experience in state government.

VDB: And we’re going to go there later in the interview.

Dunne: Yeah. And so I had to do some scrambling, pull together some of the folks on my team to talk about where we were in the process, to get them the information they needed.

And so I found myself the next morning at Blue High School, which is one of the toughest high schools in America, with a group of wonderful AmeriCorps/VISTA members all around with me. And they did this big announcement of something called “Power Up,” which was a partnership between AmeriCorps/VISTA and AOL to bring high-speed internet connections to low-income communities across the country.

VDB: Now, was this part of the same push — I remember these well-publicized events that Clinton and Gore used to do, with them running fiber-optic cable into high schools, actually wielding the cable and tools and stuff?

Dunne: I think that was the precursor to it. That was the program that helped get high-speed internet to libraries and schools. I think that’s what those events were about.

VDB: Okay.

Dunne: Bill Clinton and Al Gore both recognized that to create true equality you had to have equal access to information, and in this day and age, equal access meant high-speed internet. So they worked very hard getting it into schools, libraries, and in this case it was about getting it into Boys and Girls Clubs, and Urban Leagues, and those sorts of organizations.

So, there I was, and there was this presentation, and it was very exciting, and at the end there was this group of VISTAs who hadn’t been able to make it up to the stage to meet Clinton.

So as I came off the stage, I said to them, “Have you met the President,” and they said no, so I said, “Come on.”

VDB: Now, you had met him before this event?

Dunne: I had met him.

VDB: Did you interview with him for the [AmeriCorps] job?

Dunne: Well, I’ll finish this story, and then I’ll get to that. So I brought the VISTAs up, and I wound up in the photo, introducing him to these young, amazing AmeriCorps/VISTA workers who were all doing technology work in the DC area. And between us is a guy named Gene Sperling —

VDB: Oh yeah, sure.

Dunne: — who was the chief economist on the Council of Economic Advisors, I think, can’t remember for certain.  But one of the young people who didn’t sleep in that administration, who was dreaming up new ways to tackle issues of inequality across the country. That’s the picture. It’s a really exciting one, because it’s not just me getting to be with one of my political heroes. It’s me getting to introduce him to others who were inspired by him, and who were in the AmeriCorps program. That program was really his dream, and in many ways his legacy.

But one of the young people who didn’t sleep in that administration, who was dreaming up new ways to tackle issues of inequality across the country. That’s the picture. It’s a really exciting one, because it’s not just me getting to be with one of my political heroes. It’s me getting to introduce him to others who were inspired by him, and who were in the AmeriCorps program. That program was really his dream, and in many ways his legacy.

VDB: And which was the Republican’s obsessive target, again and again and again. You know, Clinton, when he didn’t want something to go away, he defended it like a dog with a bone. And AmeriCorps was about the most personal issue for him.

Dunne: Because it made so much sense. Bill Clinton was masterful at understanding at a visceral level what would make sense to people, what would make sense to the country, what was inspiring, and what brought out the best in Americans. AmeriCorps fit all of those things. Now, the first time I met Bill Clinton I was actually at the waterfront here in Burlington, in 1992.

VDB: This was during the general election?

Dunne: [Nodding] The general election. And Vermont was on the verge of voting for the first time in history for a Democratic President.

VDB: Is that true? It had never happened?

Dunne: Yeah. I believe so.

VDB: Wow. I hadn’t realized. I mean, I knew it had been a long stretch of time but —

Dunne: Well, at least not since Lincoln. So this was a pretty exciting time to be a Democrat.

[Editor’s note: In fact, Vermont went heavily for LBJ in 1964, to the extent that “the Democratic candidates for the lower offices (like treasurer) were carried into office even though none of them campaigned or wanted the office.” Hat tip to Chris Graff for the history.]

And I had been at Brown the year before, finishing up, and I was a Clinton guy at Brown — which put me firmly in the Right wing [laughing] on the Brown University campus.

But I had studied public policy, and I loved what Clinton was doing in Arkansas around empowerment and true welfare reform — not just doing the cutting but actually doing the child-care investment, doing the job training, to help people get out of the cycle of poverty.

And I was here in Burlington as a young Democratic candidate, because I was actually running for the [Vermont] House, inspired by Clinton. Clinton told people like me, if you don’t like the way the country’s going, get involved. So I took him literally, jumped into a race —

VDB: Which is just how he meant it.

Dunne: Yeah!

VDB: I mean, he came out of law school and jumped immediately into a Congressional race, and came within a couple of eyelashes of winning as a reform candidate —

Dunne: Right, very close.

VDB: — during that Watergate backlash.

Dunne: Right. So then I was invited to come up during the campaign, and everyone was out on this long dock, and a couple of people — I don’t even remember who — moved me up to the front of the crowd. And they said to me, “He wants you to be up here with him to be seen as part of this campaign for change.”

And it was stunning: it was this gorgeous day with the sun coming over the lake, and I went out to the end of the dock. And he was magnificent, and gave a speech about change and hope, and worked his way down the row, and took my hand and shook it and said he was glad I was running. Because I had this big old sticker on my chest that said, “Dunne for State Rep.”

VDB: Okay, this sounds like it’s completely off track, but for me it’s not. In my book when I was writing about the JFK/Clinton handshake, I tried really hard to imagine what JFK’s handshake must actually have felt like to the 16-year-old Clinton, and vice versa. So just out of pure, maybe admittedly weird curiosity, what’s it like to shake hands with the guy? What kind of a handshake?

Dunne: He has very large hands, and he actually envelopes your hands and squeezes pretty hard. He does the two-hand shake, and he also does a good political trick, which is that he squeezes first, which is —

VDB: First before what?

Dunne: First before the other guy. Which is the way to make sure that your hand doesn’t get sore over a long period of time, because if you squeeze first the other guy can’t squeeze back.

VDB: Let me jump from that handshake to — because I’m always intrigued to ask the Dean people, the people who were hard-core in that campaign, what it was like when The Scream went down. Which is to say, how did it feel as it came apart. With Clinton people, people who had formative experiences with Clinton, it’s more how did you feel when the Lewinsky scandal happened, and what’s your take-away about Clinton?

Dunne: It was a very, very painful time for me. Bill Clinton had been an inspiration, and a person I looked to for not only brilliant policy ideas but also for the kind of communication that you always dream a political leader will have. One that is empathetic, and who can connect to people from all walks of life. And for him to make the stupid decision to try to avoid a scandal by being too clever by half —

VDB: Four or five times too clever by half. In various situations.

Dunne: Right. It let me down, and many others who worked very hard for him in some fundamental ways. But it also reminded us that he was human. And there were a bunch of us who were beginning to wonder if he really was human, because he was so extraordinary in all of these other ways.

Here’s the other way that I felt let down. My first memory, political memory, is Richard Nixon in Watergate. And from that point forward there had not been a President who really articulated public service, and that the community that comes about through government could be a positive thing. You had Jimmy Carter who was savaged; you had Ronald Reagan, who ran the entire time — along with George Herbert Walker Bush — on the idea that government itself was bad.

And you finally had someone who was stepping forward and saying, in a twenty-first century model, government has a role that can be empowering, and strengthening, and vital. And going down the route of deception undermined a lot of that feeling.

And you finally had someone who was stepping forward and saying, in a twenty-first century model, government has a role that can be empowering, and strengthening, and vital. And going down the route of deception undermined a lot of that feeling.

VDB: Let me go back to what you said about Clinton, and what government can do in terms of producing community.

Dunne: And individual empowerment.

VDB: Right. Now, you’ve talked about making the Lieutenant Governor’s office an “office of action.” And as a kind of pilot project of that, you’ve been running your campaign in a different way, along the lines of what you call “service politics.”

Dunne: Yup.

VDB: So people out there no doubt have heard of the physical part of the service politics projects — where you and volunteers go clean up a park, say. Can you talk a little bit about the thinking behind those events? How is that going to work once you’re in the office, assuming you cross the line before Dubie a week from now? What’s the philosophy?

Dunne: When AmeriCorps was founded, it was founded out of a concern that young people were becoming more and more detached from society. It was a good concern. Cynicism was rising, lack of participation in the political process was rising. The hope was that through creating the expectation of service, for one or two years, we would emerge with a new generation that would be committed to giving back, through both social mechanisms and political.

What was interesting — and when I got there it was the hottest topic in the AmeriCorps world — was that in fact more and more young people were doing community service, but it appeared that the more they did community service, the less interested they were in politics.

And there was this sort of crisis of confidence in the AmeriCorps community. How could this be happening? And my assessment of it was that the more people saw that they could make a real, tangible difference in a community, the more distant the political world felt. The smaller their one vote felt. The smaller their ability to overcome the huge amounts of money that were streaming into politics.

And I think that efficacy piece is what’s so critical.

VDB: Now how does that connect to the service politics exactly?

Dunne: As I was thinking about how to bridge those worlds, what I realized is that there’s a huge opportunity to do community service, and to invite people that already connect with that kind of activity, and then bridge it to the political world.

And so when we do our service projects around the state, we don’t go and just scrape and paint windows at a museum, or go and paint the inside of a Boys and Girls Club, or go and do work in a nursing home. We also go and have conversations about cuts in arts funding, about the importance of after-school time in Bellows Falls —

VDB: At the event you have these conversations?

Dunne: At the event itself. With the director of the organization right there. And all the way through to, at nursing homes, talking about the critical need for activities directors. And what it does is that, for the people who are there, it makes them realize that the work they’re putting in at that specific location has an application in Montpelier. There are things that Montpelier could be doing more of — in some cases, things that Montpelier could be doing less of — that would allow for that local organization to be more successful in achieving their goals.

VDB: Let me, if I could, just pivot right there and — this is maybe the last reference to Bill Clinton, I can’t promise but I’ll try —

Dunne: That’s fine, that’s fine.

VDB: I’ve only ever heard one negative rap on you, in all my time covering this race, and in all my time knowing you, there’s only one real knock that I’ve ever heard. Which is fairly amazing, because with most people in politics there are a full spectrum.

Dunne: [Laughing] I could probably point you to a few more people to flesh out that spectrum, but uh —

VDB: The rap tends to be that you’re too ambitious, that you’ve moved too far too fast, that you began preparing too early, etc. And the reason I connect this to Clinton is that much the same was said of him in Arkansas, when he got out of law school and ran for Congress, and then Attorney General, and won.

So I’d like to just give you a chance to talk about this idea. Because I’ve always had a hard time seeing it, myself. I mean, if someone wanted to be, say, a javelin thrower. They wanted to be the US gold-medal-winning Olympic javelin thrower, and they began at an early point training, no one would bat an eye. They’d be seen as industrious.

Or take Tiger Woods. No one called him overly ambitious for swinging a club before he could ride a two-wheeler. But when it comes to politics, there’s a disconnect there.

Dunne: [Shaking his head] It is a subject that comes up fairly often. And I think there are a couple of things that go into it. One that not a lot of people know about me is that my father passed away when I was young —

VDB: How young?

Dunne: Thirteen. And for those who have gone through that, they know that you grow up a little faster than is normal, or than is frankly really healthy. And it places you in a position of wanting to step forward more quickly, in establishing yourself in the world and what you’re going to do.

And I also grew up in a household where my father was a passionate change agent. Where he had been involved in the civil rights movement during college — he’d actually been sentenced to two years in prison for civil rights activism, served four months hard labor in North Carolina. Some scary stories came out of that.

Then he worked for Mayor Lindsey as a special assistant on civil rights at a very young age, and then went on to be an attorney helping to found the Vermont Land Trust and Upper Valley Services.

So I had a household that believed in public service, in one mechanism or another. And that, combined with Bill Clinton showing up on the scene as I was 22, led me to run for office in my hometown district, where very few people gave me a shot at all.

And I first ran into that ambition comment, as you can imagine — people think I look too young now — you can imagine when I would show up at their door at 22. And they would try to ask sly questions to find out how old I was, like “Are you, uh . . . married?” And I’d say, “Nope, haven’t found the right girl just yet,” and they’d give me a look and the conversations would go on. And they’d give me the benefit of the doubt, and vote for me.

So what I decided was that the flip-side of ambition was hard work. And that as long as I was committed to giving 110%, the accusations of ambition would go away. Because ambition has a connotation that it’s about achieving power for one’s own gain.

But if you demonstrate that you’re willing to work to empower other people, whether it’s the people you’re representing or it’s getting young people involved in the political process through [Tony Gierzynski’s] Policy Research Shop at the University of Vermont, or it’s doing service politics, then you start to erase those quick impressions of ambition.

VDB: Yeah, I think by and large you’re right. But I do think it’s a charge that never goes entirely away. Clinton never escaped it altogether. Because a lot of times it’s the rationale for people who are on the ladder a generation ahead.

It’s a human thing: people, maybe particularly politicians, feel that they’ve waited their turn on the ladder, and that once people above them have vacated the upper rungs, it’s understood that they’ll move into those positions — regardless really of what voters want, or who’s better positioned to win, or to serve. It’s a feeling that pervades establishment politics.

I love the idea that your primary victory, and TJ Donovan’s really convincing victory in the primary, visibly opened that door. Because I think it says to people in their thirties, as you both are, there’s no reason why if you feel so moved, and voters feel so moved, that you shouldn’t take advantage of your moment.

Okay. We started with vision and we’re slowly moving to questions of hard-core strategy. In the primary, you did something that seemed, at the time, either altogether inspired or altogether stupid: you held back much of your resources — direct mail, television advertising — until the last ten days of the contest. And you wound up with a fairly lopsided victory, a sixteen-point victory, when all was said and done.

So I’ve come to the conclusion that it was, in fact, an inspired strategy [Both laughing] in the way that hindsight will do for you.

Now some people looking at this race — and I think Peter Freyne put it pretty succinctly when he asked if the Dunne wave would be too little too late — might think you’re still too far behind, given the calendar. I’m guessing you have a rather intricate strategy for the last ten days. You have more money on hand than Dubie does. So without telegraphing too much of your strategy, but telegraphing a lot of it for my readers[Dunne cracks up again], what’s going to happen and how is it going to lead to you pulling it off on November 7th?

Dunne: I wish I could say that I had a fool-proof strategy. But in a Lieutenant Governor’s race, it’s always difficult to get people to focus on it, especially when there are other races that are higher profile and contested. It’s also difficult to raise money.

And there we’ve been fortunate to have garnered support from thousands of people to support the campaign. The strategy in both cases has been to do a lot of grassroots work, knocking on thousands of doors, doing community service projects, making those phone calls. And then — when people actually start to pay attention — making our message clearly and effectively.

In the primary, the challenge was that people don’t start paying attention until after Labor Day. So we knew that we should do all that groundwork ahead of time, but hold our fire until that period right before Election Day, when we understood people would be focused. And we also knew that we could utilize our small amount of financial resources to make the maximum impact.

In this case, what has been fortunate is that the races around us have fallen in the ways we expected them to —

VDB: How do you mean?

Dunne: We assumed at this point it would be clear who was winning the US Senate race, it would be fairly clear who was winning the Congressional race.

VDB: Leaving a media vacuum.

Dunne: [Nodding] That would allow for this race, in which we’d used interesting grass-roots strategies like service politics, to start to catch on as something a little different.

And then we would be able to implement a communications plan once people were open to a new way of doing politics, a new message, and a race that hadn’t shown up yet on the radar screen.

VDB: And you have internal polling, just released, that shows your race tightening — the gap was over 25 points, and is now within 15.

Dunne: And more importantly, the incumbent in a head-to-head is at 44 percent, with 90 percent name recognition, while I only have 50 percent. So if that many people know who Brian Dubie is, and are unsure that they want to vote for someone who has his extreme values — which are as he put it “George Bush Republican” — or someone who is not utilizing the office to its fullest extent, that’s very good for us.

VDB: Let me ask you about Dubie’s strategy, to the extent that one could use the term, because I really think it’s been a deliberately unrun race, with almost nothing in the way of traditional meet-the-voters events. If you throw in the two weeks in Iraq, a trip which seems to have been put together with at least one eye on the political calendar, then it seems to be about avoidance, and depriving the race of a microphone.

So if you could, what are the two or three under-reported points of information that you would have liked to have gotten out by this point, but that just haven’t been covered because of that Rose Garden strategy on Dubie’s part.

Dunne: Let me first comment on his deployment. Because I know you’ve written a lot about it —

VDB: And skeptically.

Dunne: And you have been skeptical about it. And I want to be really clear that my worry about that deployment was less about him being deployed, because I to this day do not believe that Brian Dubie would get himself deployed for political purposes. And, you know, I will defend anyone’s right to go and serve in the National Guard, from any job, at any time.

What disturbed me more was that the level of cynicism — in the country! — is so very, very high that the timing of the press release —

VDB: Primary night.

Dunne: — Primary night, set off all those alarm bells. And that to me says how far we have fallen in politics that that’s the immediate reaction.

It’s an interesting dynamic. I mean, part of the reason I’m running is that I want people to have faith again in people who are running for office, so that the public’s immediate assumption won’t be that their motives are nefarious and strategic.

But the things that I don’t think have gotten out there well enough? My passion for economic development, for one. I have spent most of my eleven years as a legislator focusing my attention on strategies for creating jobs in the state of Vermont that don’t compromise our farms and forest lands and traditional way of life.

VDB: High-tech, many of those jobs.

Dunne: Many of them high-tech, but most of them around innovation, which can be agriculture, as well as energy development, so it’s across the spectrum. It’s one of the things that attracted me initially to Bill Clinton — he was a Democrat who was passionate about innovation and job creation.

VDB: Growing the economy.

Dunne: Absolutely. And I also had the opportunity to work for a company called Logic Associates, which was the classic example of two entrepreneurs who got together in Vermont and figured out a way to create software that would help commercial printers be more efficient. I had a chance to be their marketing director as the company grew to eighteen and a half million dollars in sales.

And that story — and the work that I have done using that experience to bring broad-band to the last mile of every community, to create the Vermont Film Commission — is something that hasn’t gotten out there. Largely because Brian Dubie has not been very willing to debate.

VDB: Now, just to jump in there: you did have a debate last night.

Dunne: Yup.

VDB: I know that you tried to get him to answer certain questions last night, that he refused to answer, which fits into this category of — to put it bluntly — what Dubie won’t let be said. What were those questions that he refused to answer?

Dunne: Well, I thought that in this day and age, with everything that’s going on with the Supreme Court and with the legislation just passed in South Dakota, that the issue of a woman’s right to choose is again an important issue at the state level. Because there is a significant likelihood that the issue of a woman’s right to choose is going to be thrown back to the states in the not-too distant future.

And I felt it was very important that Brian Dubie has been absolutely clear — and he actually says, “I’ve been clear on this” — that he opposes a woman’s right to choose. And in a different debate, he wouldn’t count out a South Dakota-style absolute ban.

VDB: And I’m sure in his mind, it’s not purely theoretical: he’s thinking, I may well be governor when that possibility comes to fruition.

Dunne: And it’s in the mind of many of his backers and supporters. And I feel it’s very important that it’s in the forefront of the minds of voters as they head into this election.

Because it is a different time. A different time nationally than it was four years ago.

VDB: Now, is it true, as I read today, that Dubie came out in favor of the legislation that Bush just signed on interrogation, including the so-called “alternative methods” which the White House pointedly refuses to describe?

Dunne: It is true. And what I thought was interesting is that this is a person who has highlighted his military connections as part of what he brings as a leader, as well as his international work. This person was willing to support legislation that would allow George W. Bush to determine not only whether a person was entitled to a trial, but what was allowable in terms of torture — which does not fit into the Geneva Conventions, at all. It was legislation that was decried by Senator Leahy as one of the most aggressive attacks on the Constitution, yet Dubie was willing to say, that’s fine.

And again, if the Lieutenant Governor’s office is simply a place for one to do ceremonial activities and some high-profile travel and to train to be the Governor — and this is how Brian Dubie has described it — then it’s important that people know what his views are.

I’m giving a different vision of the office. I’m talking about making it an office of action, willing to stand up against warrantless wiretapping, against affronts to the Constitution on torture and habeus corpus.

VDB: And these days, I’m of the opinion that every candidate for every office — from President down to High Bailiff of your local town — should be asked, How do you feel about torture and wiretapping? And when people say, “Well, the Lieutenant Governor won’t have anything to say about wiretapping,” I beg to differ. We all have things to say about it. Governor, Lieutenant Governor, Houses, Senates, legislatures all across the country should be speaking out about these things.

Okay, let me go to what is perhaps the final strategic consideration, a guy named Marvin Malek. I know you’ve spoken quite a bit with Malek, and that you and he don’t differ all that much in the way you see, for instance, the health care issue.

Dunne: Right.

VDB: My [Struggling for the right word] fantasy is that the two of you sit down in a room, and Malek says, “Look, I haven’t been able to generate a groundswell of support, but I could do a lot of effective work with you on health care once you’re Lieutenant Governor,” and you agree to work together. Have you had those sorts of discussions? Is this sort of thing possible, to avoid the sort of fragmented votes that put Dubie in the office in the first place?

Dunne: Marvin and I have been getting along great. And we’ve had an opportunity to get to know each other, since the two of us are actually showing up for debates [Chuckles] in all corners of the state. So we’ve had a wonderful chance to have a conversation, and a conversation about the democratic process. And if people think I’ve been harsh about Brian Dubie treating the democratic process the way he treats the office [of Lieutenant Governor], not showing up, then they should talk to Marvin.

Because he is in this. Not because he believes that he is going to win the Lieutenant Governor’s race, but because he desperately feels there needs to be a strong voice for moving forward on true health care reform. And I don’t blame him.

So he and I have been in touch. We’ve talked about the vision for the office, and I am hopeful as well that people will see that my passion for change is similar to Marvin’s — it just comes with a different experience set, and one that prepares us to be able to work together. With me as Lieutenant Governor, and Marvin as an extraordinary mind working toward health care reform.

VDB: That’s I guess where the fantasy part comes in. If you look at your internal poll, Malek was at 4 percent, but let’s call it double that — 8 or so. Let’s say you wind up with 44, and Dubie winds up with 47 or so. A few points of margin. To my mind, that’s a tragedy, because — and I agree with you, Marvin Malek has some excellent things to say.

But unfortunately Brian Dubie has been the recipient of that third party challenge more than once. It basically put him in office, and it may well keep him in office. And so my mind strategically goes to that moment.

So for instance, I imagine that with ten days left, if you and Dr. Malek came out and said to the media, “Look, we’re seriously considering joining forces here, give us a few days to finish our discussion,” there would be an explosion of stories about that. And if, after that, Malek announced that he was backing you, I think the coverage of that joint declaration could put Brian Dubie out of business. And while I wouldn’t say that Malek holds the outcome in his hand, it’s really not far from that at this point.

I think you’ve been very moderate and welcoming in your approach to Malek’s candidacy, but is there frustration there? That a good opportunity to take the Lieutenant Governor’s seat back from the GOP might slip by for good but finally misguided motives?

Dunne: There has, certainly, been frustration. But frankly the earnestness Marvin brings to the campaign defuses a lot of that frustration. Because he’s really in this for the right reasons, even if the impact may result in something that neither of us want.

It’s been an opportunity for me to say how badly we need comprehensive health care reform, and to let Marvin be articulate about the details. It’s been actually a pretty good partnership.

But we are committed to stay in touch through the final days of the campaign.

VDB: I like to make the analogy to the Presidential primary process. Everybody runs their own campaign, and pursues their own vision, but there’s a certain moment when you realize that you’re not going to get it done. And then you have a chance to endorse the stronger candidate.

Or even beyond that, there’s sometimes a moment when you can sign on as the Vice-Presidential candidate. You join the team, and you influence the general race and the administration if you win as a team. There’s an alchemy between the two candidates, in other words.

I actually see this situation as a similar thing. Malek has done a very solid job keeping the issue of health care alive, but I actually think he could end his candidacy with an extremely dramatic statement about the importance of health care, by endorsing you and possibly putting you over the top.

He could say, “Look, it’s very difficult as a Progressive to end an outside bid like this, but Matt will do a hundred times what Dubie will, and I want to work on the nuts and bolts with him to get something actually accomplished.” That would reflect well on both parties, and on the issue itself, which is the point. It might be a way for Progressives and Democrats to think about how to advance their shared agenda, without disabling either party structure or enabling the GOP.

So anyway, that’s enough about my fantasy.

Dunne: [Pausing and then smiling broadly] And it’s a beautiful fantasy.

on November 1st, 2006 at 2:01 am

[…] Just take some time to read Philip Baruth’s excellent long interview with Mr. Dunne. And see why he not only has the intelligence to be a solid performer in the office, but a clear vision of what he wants to do — and an admirable philosophy of how public service can be far more than just a career goal. […]