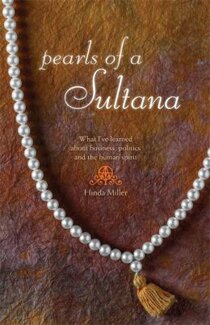

The Dao of Hinda: Reading Hinda Miller’s PEARLS OF A SULTANA

Pearls of a Sultana: What I’ve Learned

About Business, Politics, and the Human Spirit

Hinda Miller

Public Press/$19.95

Early on in Hinda Miller’s Pearls of a Sultana – an openly devil-may-care text that asks to be shelved simultaneously in the memoir/politics/spirituality/business-self-help categories – we run across a brief moment that perfectly encapsulates the work at hand.

It’s a bit of reminiscence from Miller’s ten-year term as a Vermont State Senator, specifically her early days on the powerful Senate Appropriations Committee. Having just joined the committee, and recognizing the gaps in her own knowledge, Miller begins earnestly trying to educate herself by asking questions, questions about how the committee works, questions about individual budget items before them.

It’s a bit of reminiscence from Miller’s ten-year term as a Vermont State Senator, specifically her early days on the powerful Senate Appropriations Committee. Having just joined the committee, and recognizing the gaps in her own knowledge, Miller begins earnestly trying to educate herself by asking questions, questions about how the committee works, questions about individual budget items before them.

And along with the other strings of questions, Miller has the audacity to question a particular earmark aimed at the burgeoning composite industry in Bennington.

Why, exactly, is this an audacious move?

Because, as anyone in the Statehouse will tell you, the composite industry in Bennington – like all industry and public infrastructure in Bennington – is constantly and jealously guarded by one Richard Sears (D-Bennington). Sears is an impressively large man with a very gruff voice, an acknowledged force of nature, and the flow of legislation generally moves in sympathy with that force. When it does not, the skies darken:

“I say something that bothers him. He leans forward and bellows, ‘Are you saying I don’t know what I’m talking about?’ The skin tightens slightly around his cheekbones. His nostrils flare slightly. Once more, he leans toward me. It looks like he’s ready to blow.”

And under the existing rules of engagement in the Senate, Sears would have blown, and Miller would have been incinerated in the blast – at least procedurally speaking. But unbeknownst to the senior Senator from Bennington, the junior Senator from Chittenden has powers of her own:

“I decide it’s time to change the energy in the room. The best way I know to do this is through the techniques I learned in my recent Naam Intensive. I begin moving my arms in a sinuous fashion around my head and shoulders. (It’s a motion you sometimes see with belly dancers.) I am moving the energy from the earth to the heavens, as I have learned from my yoga studies.

“At first Sears tightens further. He is taking this very personally, not my intent. He is interpreting this as mocking or criticizing. ‘Are you criticizing me?’ he sputters. I shake my head. He looks at me as if I am having a stroke . . . . After a period of stunned silence he sputters, ‘What . . . are . . . you doing?’

“’I’m changing the energy,’ I say.”

And incredibly enough, it works (at least in Miller’s version of the tale). In the very next moment, Sears breaks into a hearty laugh, and the tension melts. Whether Sears relents because he honors the Kabbalist principles behind Miller’s gestures – or because he thinks Miller is stark-staring mad and must be humored – matters not at all. The important thing is that the default mode of thinking has been interrupted, and productively so.

And that, after all, is Miller’s intention in Pearls of a Sultana.

Miller knows very well that her attempts here to join Kabbala and yoga and numerology to the worlds of business and politics will be met with skepticism, even hostility; she knows that the book’s structure and tone are wildly idiosyncratic; she knows that she is not proposing a neatly numbered set of steps to improve business efficiency; and she knows that all of these things will inhibit the number of books she ultimately sells.

Miller knows, in short, that readers may well react the way that Dick Sears reacted to her sudden sinuous arm movements – but she’s betting that even if they do, they’ll wind up in a new (and potentially productive) mental space as a result.

And speaking only for myself, it works.

You’d be hard pressed to find someone less receptive to numerology than me, to take one example; it has always struck me, like astrology, as a pseudo-scientific means to discover that the universe shares your own deepest desires. And when it creeps into Miller’s text here, I can’t help but roll my eyes: “There are 12 sections to this book. 1+2=3. The number three is ruled by Jupiter, the lord of the planets who brings prosperity and growth, and good luck.”

But having rolled my eyes at the numerological whimsy, and with my expectations in flux, I’m then doubly impressed when the text shifts gears to a wonderful, sustained, first-hand account of the founding of Jogbra. For those interested only in hard-core business advice, and the anecdotes through which it is traditionally offered, the Jogbra chapters will be more than worth the price of admission, in and of themselves.

Of particular interest for would-be entrepreneurs? The detailed break-down of Jogbra’s initial financing structure, how the two-person company scaled up before being ultimately acquired by the Sara Lee Corporation.

As with the Sears story, Miller succeeds as a Jogbra entrepreneur partially (but importantly) because of her own willingness to admit ignorance, to ask questions, to trust where pure reason might dictate skepticism. Much the same is true of her equally intriguing account of the early years of Green Mountain Coffee, on whose board she continues to serve. In her telling of it, she succeeds the way that Cain succeeded in every episode of the old Kung Fu series: by presenting an open heart, by dint of human connections, and by fighting only when peace can be had no other way.

In that sense, Miller comes across as a highly enthusiastic networker but a reluctant corporate warrior, one whose great success argues that perhaps the idea of business as war has always been substantially overvalued.

(And of course this reluctant warrior happened along at the perfect historical moment, at least here in Vermont – Miller’s emphasis on networking, community, partnership, gentleness and good intentions was the right note to hit in a state increasingly cognizant of corporate responsibility and social mission.)

If you come to the text searching for a hard and fast definition of “sultana,” you will be disappointed, however, for Miller makes no bones about the fact that the concept is a work in progress. “Is it a club,” she asks, along with the reader, “a movement? A product line? Time will tell. And I, for one, look forward to finding out.”

Whatever else it might be, the concept is clearly an attempt to create more and better ways of thinking about women of a certain age: “Think of the English words for an older woman – ‘Biddy,’ ‘bitch,’ ‘hag,’ ‘crone.’ Wouldn’t you rather be a ‘Sultana’?” But even the book’s feminism is fluid and situational, one of a number of ways of successful thinking, rather than an analytical tool to be applied dutifully in each and every scene.

Miller, with Senators Illuzzi, Campbell, and Hartwell.

Part of the point with this new book, as with Miller’s undeniable success in business, is that she remains determined not to overdetermine. She believes, apparently with every fiber of her being, that a selfless heart and a questing mind – and a lifelong yoga regimen – will bring not only happiness, but riches as well.

And honestly, can I say that my previously mentioned disdain for numerology has ever brought me either one?

Reader, I cannot.

The fact is that to this day, when things grow confrontational in the Vermont State Senate, you will still occasionally see a senior Senator here or there begin to move their arms in trademark Hinda fashion, moving the energy from earth to the heavens, with other senior Senators quickly joining in the joke, half mocking the gesture as they do so, but invoking it nevertheless as a way of indicating that everyone needs to take a deep breath and refocus. I’ve seen it with my own eyes, many times.

And in that, yogi Miller has succeeded beyond her wildest dreams.

This, then, is the dao of Hinda: Laugh if you will, for your laughter serves only to enrich us all.