I’ve been both a novelist and a political junkie for as long as I can remember. At least as early as 1976, at age 14, I was doing both simultaneously: writing a staggeringly bad book of fiction, and placing last-minute get-out-the-vote calls during the presidential campaign that put Jimmy Carter in the White House.

Now, at age 45, that schizoid rhythm marks the official structure of my life. By day, I write, read and teach novels; at night, I live-blog debates and primaries, and read online newspapers into the small hours.

But of course the two worlds cannot remain distinct. Far from it.

As the years have accumulated, my fiction has been markedly colored by politics. And because of my day job as a fiction writer, I have evolved into a very particular kind of political junkie.

I like complex political characters, in short.

Take George W. Bush. Long story short, I don’t like him.

But part of the reason I don’t like him — the deepest reason of all maybe — is that he is badly drawn, as a human figure. The man is as nearly two-dimensional as it is possible for a living person to be.

Of course, lacking a third dimension helped immensely post-9/11: it made Bush seem a character straight from the pages of DC comics, a superhero, a graphic creation defined at its most basic level by flatness.

(At the risk of stating the obvious, Bush could never cut it in the Marvel universe, where heroes brood and wrestle inner demons.)

Once Iraq exploded, though, Americans became nostalgic for depth.

But even then Bush’s two-dimensionality came in surprisingly handy. When out of his depth at press conferences, Bush could always do the rhetorical equivalent of turning sideways — repeat five or six untethered phrases until reporters quit in disgust — allowing him to all but disappear.

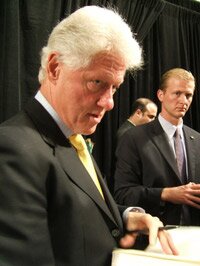

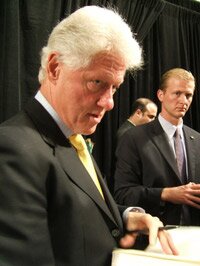

You want a complex character? Bill Clinton was a complex character.

You want a complex character? Bill Clinton was a complex character.

What Clinton and Dick Morris would eventually label “triangulation” was first and foremost a strategic imprint of Clinton’s own psyche: here was a kid who had lost three fathers by the time he reached the age of 35, and for whom elections and polls would always supply an obsessive need for approval.

Again and again, this need for approval led Clinton to shuffle as close to the Republican Party as he could get without being physically repelled.

Clinton explained with great patience that he was merely shop-lifting as many GOP issues as he could fit into his pockets, as a way of winning re-election, which would give Democrats their first two-term President in decades. And these moves eventually secured Clinton approval from 60% of the American people, just enough to see him through the trials of impeachment.

But it was more than strategy.

The truth is that Clinton couldn’t abide the thought of the remaining 40%, the followers of Newt Gingrich and Dick Armey, the millions who despised their President.

And so he was constantly using one excuse after another — re-election, the budget standoffs, reaching across the aisle — to give Republicans what they wanted, without quite losing his loyal Democratic base.

Hence Don’t Ask Don’t Tell. Hence Mend It Don’t End It, Clinton’s patchwork on affirmative action. Predicting Clinton was a fool’s game. And policy-wise, it was maddening.

But it was fun to play, even so. Which brings us to our own complex political character: Peter Shumlin.

Shumlin began this legislative session with a move so bold it scrambled every political calculation instantaneously: he placed meaningful legislation on global warming at the top of his Senate to-do list.

Suddenly, everyone — Transportation, Natural Resources, Economic Development, Gaye Symington, Jim Douglas, everyone — was forced to regroup.

And almost immediately thereafter, Shumlin staged a press conference with the Governor during which he agreed with Douglas that the property tax conundrum could not be solved by raising new revenue. It was a spending problem, first and foremost.

In other words, only days into the session, Shumlin had placed everyone in the State House in a very tight box, made up of walls sacred to the Left and to the Right. And most of the work attempted or accomplished this session occurred within the tight confines of that strategic box.

No one was more inconvenienced by Shumlin’s pincer tactic than Shumlin, of course.

The friction between global responsibility and local frugality was inevitable, and that heat occasionally forced Shumlin into damage-control.

After arguing that the tax burden on Vermonters was already punishingly heavy, for instance, Shumlin was forced retroactively to argue that he’d never meant to say he couldn’t raise “small taxes to take care of pressing problems for Vermont.”

Still, on balance, Shumlin’s moves were bold enough, popular enough, and unpredictable enough to play havoc with the Governor’s center of gravity.

And partially as a result, Douglas looked as unsteady this year as he has since coming into office.

Then came impeachment.

It began directly enough. In no uncertain terms, during a long interview in his office at the Statehouse, Shumlin told me that he supported impeachment, supported it eagerly: “I think it would be a great thing for Vermonters to move forward on the impeachment process.”

Without rehearsing the minor variations of the rhetorical dance that followed, it’s fair to say that Shumlin then reversed positions twice, vehemently in each case, finally coming 360 degrees back to the position he quitted for no apparent reason when it became clear that an impeachment resolution could originate in the Senate as well as the House.

Predicting Shumlin, then, was a fool’s game.

But one interpretive frame works as well or better than any other: all of Shumlin’s moves this session dovetail with a statewide run for Governor, up to and including the final pirouette on impeachment.

Having double-crossed activists, only to serve then as their imperfect champion, Shumlin came as close to making the issue a wash as he was humanly able.

And not every mainstream Democratic politician has been or will be so lucky.

Still, the back and forth had the potential to make you a bit nauseous — or a bit nauseated, depending on your political persuasions. Watching Shumlin work was like watching Clinton work, which was always like watching an exotic dancer work: there was always something simultaneously artful and accomplished and undeniably seamy about it.

But the last, greatest miracle of Bill Clinton was that just when you had all but given up on him, he would produce something truly fine in the way of public policy, or an appointment to the Court like Ruth Bader Ginsberg, something well worth the price of admission in and of itself.

Shumlin is no different. Here in the last weeks of the session, he constructed one of the most ingenious interlocking strategies in modern legislative history. His last best hope for meaningful global warming legislation — an expansion of Efficiency Vermont to target fuel savings in buildings — Shumlin proposed to fund with a windfall profits tax on Vermont Yankee.

Given that Shumlin has also proposed moving Vermont Yankee nuclear waste to the state’s most populous counties — as a way of fomenting opposition to the plant’s relicensing in 2012 — the windfall profits tax seems like an elegant solution to two intractable problems.

It will expand an energy-efficiency program praised on both sides of the aisle; the newly expanded agency will help Vermonters lower their fuel costs; energy efficiency will significantly reduce Vermont’s carbon signature; and the only people who will pay through the nose are those running an aging nuclear plant that should have been shuttered years ago anyway.

It’s brilliant. Complicated and more than a bit tricky, but brilliant.

And in the final analysis, that’s all I’ve ever asked from any political character.

[This piece appeared first in the Vermont Guardian.]

Bill O’Reilly, in his continuing bid to paint Vermont as a “secular progressive” lab experiment run amok, sent a crew to the State House to mug Lippert, whom they accused of being soft on sexual predators.

Bill O’Reilly, in his continuing bid to paint Vermont as a “secular progressive” lab experiment run amok, sent a crew to the State House to mug Lippert, whom they accused of being soft on sexual predators. Imagine the scene over at the No-Spin Zone: O’Reilly’s producer spots the Wellstone connection, the connection to the current Vermont House and Senate Leadership, and a single drop of saliva rolls from his unkempt upper lip down the length of one long tartar-brown canine tooth.

Imagine the scene over at the No-Spin Zone: O’Reilly’s producer spots the Wellstone connection, the connection to the current Vermont House and Senate Leadership, and a single drop of saliva rolls from his unkempt upper lip down the length of one long tartar-brown canine tooth. This thanks, in no small part, to the indefatigable David Zuckerman, who pulled us aside a few weeks back to whisper, “My fingerprints aren’t on the bill,” then add with a smile, “but my fingerprints are all over it.”

This thanks, in no small part, to the indefatigable David Zuckerman, who pulled us aside a few weeks back to whisper, “My fingerprints aren’t on the bill,” then add with a smile, “but my fingerprints are all over it.” In the meanwhile, Tony Gierzynski has folded his ground-breaking IRV exit polling — conducted during Burlington’s last mayoral race — into a readable, thoughtful on-line article for Campaigns & Elections.

In the meanwhile, Tony Gierzynski has folded his ground-breaking IRV exit polling — conducted during Burlington’s last mayoral race — into a readable, thoughtful on-line article for Campaigns & Elections.

You want a complex character? Bill Clinton was a complex character.

You want a complex character? Bill Clinton was a complex character.

David O’Brien, head of the state’s Department of Public Service, takes it on the chin especially hard. Porter has Senator John Campbell on the record, calling foul in the fight over the energy bill.

David O’Brien, head of the state’s Department of Public Service, takes it on the chin especially hard. Porter has Senator John Campbell on the record, calling foul in the fight over the energy bill. “O’Brien did not dispute that the exchange took place. But he said he never intended Campbell to feel threatened.

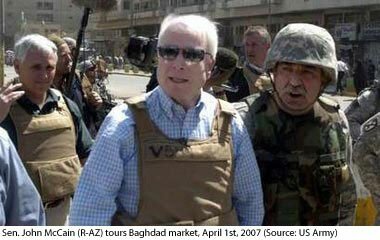

“O’Brien did not dispute that the exchange took place. But he said he never intended Campbell to feel threatened. “BAGHDAD, May 10 — A majority of members of Iraq’s parliament have signed a draft bill that would require a timetable for the withdrawal of U.S. soldiers from Iraq and freeze current troop levels. The development was a sign of a growing division between Iraq’s legislators and prime minister that mirrors the widening gulf between the Bush administration and its critics in Congress.”

“BAGHDAD, May 10 — A majority of members of Iraq’s parliament have signed a draft bill that would require a timetable for the withdrawal of U.S. soldiers from Iraq and freeze current troop levels. The development was a sign of a growing division between Iraq’s legislators and prime minister that mirrors the widening gulf between the Bush administration and its critics in Congress.”