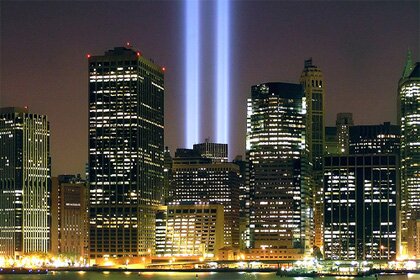

The 9/11 Attacks: Thoughts Then and Now

I can’t help but remember that the first attack on the World Trade Center took place on February 26, 1993, just a month or so after Bill Clinton took office. And 9/11, after years of planning, was executed in the first months of George W. Bush’s term. The pattern suggests three things to me: 1) Al Queda prefers to debut their current tactics as we debut a new President, to offer the world an extremely high-profile counterpoint; 2) their largest plans in this country germinate over long periods, but roughly 8 years in the last instance; and 3) it’s now been about that long, again, and we happen to have a shiny new President in D.C.

Not to be an alarmist, but Al Queda is a terrorist organization with a strangely compulsive attention to pattern, repetition, spectacle and detail. It makes me just a little jumpy today, thinking about it, maybe especially since I’ll be getting on a trans-Atlantic flight this weekend. You have to hope that the Presidential Daily Briefings are actually being read, and pondered, in the White House these days.

In any event, here’s a piece I wrote for Vermont Public Radio just a few days after the attacks of September 11. Stay safe, all of you. — PB

Announcer: Commentator Philip Baruth has been struck by the stories that we tell one another in the face of tragedies like those in NY and Washington, how those stories seem part of a larger plan.

Notes from the New Vermont

Commentary #67: Bracing the Buildings of the Mind

I can tell you exactly, to within five or six inches, where I was when I heard about the Oklahoma City bombing — I was in my old 1986 silver Toyota pickup, stopped at the red light at the head of Church Street in Burlington. It’s one of those red lights that chirps to tell pedestrians it’s safe to cross, so there was this safety chirp in the background.

The radio announcer said only that there was a report of a terrorist leveling the Murrah Federal Building with a truck bomb, and that maybe as many as a hundred were dead.

I remember also that from where I was idling I could look down the length of Church Street at the people shopping and loitering in the sun and I remember thinking that probably I was looking at about the same number of people, about a hundred, give or take.

Later I found out that the death toll in Oklahoma City was 168, and that the blast was touched off by a Persian Gulf veteran named Timothy McVeigh. But none of the information that came later matches the strength of that first memory: where I was when I heard, what I was doing when the news reached me.

It was the same with the September 11th attacks on New York and Washington. By the end of the day, I’d told the brief story of where I was and how I’d heard ten or fifteen times — to my sister in California, my mother in New York, my friend Joe in South Bend, Indiana, to the people I work with at the University of Vermont.

And all of those people had told me their stories, where they were, precisely where they were and what they were doing.

By the end of the day all of us, everyone I know, had their story written and rehearsed and committed to memory. And I started wondering about these little “where I was” stories, wondering why they’re so universival and so seemingly crucial at a moment like that.

And the nearest I can figure is that it’s a process a lot like the way the body stops bleeding, through coagulation, blood clotting. When your skin is torn, individual blood platelets start attaching to the wound, releasing chemicals to constrict vessels and staunch bleeding. Eventually enough platelets join together to close the injury.

And when your view of the world is ripped open by the sight of an airliner plunging into a skyscraper and the skyscraper then collapsing, impossibly, to the ground, the mind responds just like the body: with small overlapping stories in which you know where you are, in which you are safe, and in which the world is a stable place.

Sure, the stories seem to be about your first experience with new trauma and chaos, but they’re also a way of reinforcing the stable aspects of the world.

A “where I was” story is also just an “I was” story: I was alive, I was okay, even though elsewhere in the world far too many others were not alive and okay. A “where I was” story is immediate mental self-preservation.

By the end of the day your small story has been added to the many small stories of your friends, and together they form a combined story in which the trauma at the center is surrounded by a suddenly vast and reassuring margin. And that frees us as individuals to return to help those in greater need.

I’m a writer by trade, and stories are what I deal in day to day, but the power of story itself had never struck me quite as forcefully as it did last Tuesday night.

I thought about what I’d seen all day — the cell-phones that were suddenly everywhere, people talking and gesturing to networks of invisible friends, and the little knots of people stopped at odd places in hallways and on the street, everyone occupied in something both perfectly natural and perfectly miraculous: the telling of reality, and the necessary retelling of normalcy.

Some people see the divine in the petals of flowers, or the super-subtle mechanics of childbirth. For me, the divine is a story. It’s a story that comes unbidden, and braces the falling buildings of the mind.

[This piece aired first on Vermont Public Radio.]